Every decade or so, Robert likes to check in with the Monty Hall problem. You may have heard of it. If not, you can read all about it here at wikipedia.

From Wikipedia:

The Monty Hall problem is a brain teaser, in the form of a probability puzzle, loosely based on the American television game show Let’s Make a Deal and named after its original host, Monty Hall. The problem was originally posed (and solved) in a letter by Steve Selvin to the American Statistician in 1975 (Selvin 1975a), (Selvin 1975b). It became famous as a question from a reader’s letter quoted in Marilyn vos Savant‘s “Ask Marilyn” column in Parade magazine in 1990 (vos Savant 1990a):

| “ |

Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice? |

” |

Vos Savant’s response was that the contestant should switch to the other door (vos Savant 1990a). Under the standard assumptions, contestants who switch have a 2/3 chance of winning the car, while contestants who stick to their initial choice have only a 1/3 chance.

Many readers of vos Savant’s column refused to believe switching is beneficial despite her explanation. After the problem appeared in Parade, approximately 10,000 readers, including nearly 1,000 with PhDs, wrote to the magazine, most of them claiming vos Savant was wrong (Tierney 1991). Even when given explanations, simulations, and formal mathematical proofs, many people still do not accept that switching is the best strategy (vos Savant 1991a). The problem is a paradox of the veridical type, because the correct choice (that one should switch doors) is so counterintuitive it can seem absurd, but is nevertheless demonstrably true.

Robert likes to revisit the problem from time to time in order to refresh his very thin grasp on Baysian probability. Each time he looks at the problem, he satisfies himself that he understands the solution. But then, of course, he soon needs to figure it all out again.

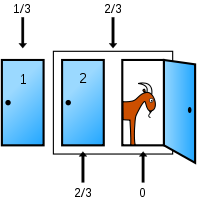

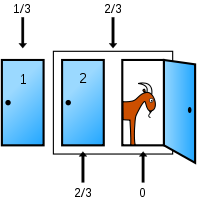

Actually, Robert will say that of all the explanations of the problem, these images from Wikipedia are the best for him.

Car has a 1/3 chance of being behind the player’s pick and a 2/3 chance of being behind one of the other two doors. The host opens a door, the odds for the two sets don’t change but the odds move to 0 for the open door and move to 2/3 for the closed door.

What is so absolutely awesome, Robert has come to learn, is that the vos Savant episode, which introduced the problem to a mass audience, occurred at the exact time that the field of behavioral psychology was coming into swing. You know, of course, that there have been a few recent Nobel Prize winners in that field. The problem demonstrates exactly the kind of thing that behavioral psychologists like Daniel Kahnaman, et. al have been telling us for about twenty years. That humans really suck at statistics. Especially, for example, Baysian probability.

So, it turns out that over the last ten years there have been some really neat papers trying to explain why we suck at the Monty Hall problem (since renamed by academics as the Monty Hall Dilemma (MHD)) and what we might do to get better at it.

For your nighttime reading pleasure:

Monty Hall’s Three Doors for Dummies, Morone and Fiore, 2008 read.

The Monty Hall dilemma in pigeons: Effect of investment in initial choice, Stagner, et. al, 2013 read.

Testing the limits of optimality: the effect of base rates in the Monty Hall dilemma, Herbranson and Wang, 2013 read.

Reasoning and Choice in the Monty Hall Dilemma (MHD): implications for improving Baysian reasoning, 2015, Tubau,

et al. read.

Robert just read The Once and Future Liberal, After Identity Politics, by Mark Lilla. Lilla is a professor of humanities at Columbia who writes books on modern politics and philosophy (including one about Isaiah Berlin written with Ronald Dworkin). This short book was born out of an article Lilla wrote after the 2016 Presidential election arguing that the Democratic party needs to move away from its focus on race, gender, and other personal identity divisions as an organizing idea. It is a very quick read.

Robert just read The Once and Future Liberal, After Identity Politics, by Mark Lilla. Lilla is a professor of humanities at Columbia who writes books on modern politics and philosophy (including one about Isaiah Berlin written with Ronald Dworkin). This short book was born out of an article Lilla wrote after the 2016 Presidential election arguing that the Democratic party needs to move away from its focus on race, gender, and other personal identity divisions as an organizing idea. It is a very quick read.